The Time Magazine cover was reshared by many after the recent killing of George Floyd. Why is it so important for people to document moments like this in history, and can you share any advice to young photographers looking to leave a lasting impact?

I think documenting any moment is beyond just that moment itself. What I’ve learned from being on the ground, starting five years ago through today, is that I’ve evolved myself. Documenting the work is very important, not to commercialize it, but for history. This is for the history books. What I was documenting back in 2015 came from the point-of-view of a concerned citizen. I just wanted to tell a story, because a lot of times stories can get misconstrued in the media. Us telling our own stories and sharing those stories is very important, especially as we live through moments like we are now. It’s not about an individual taking photos, it’s about individuals documenting real moments for the people. You have to make sure you put your ego aside to tell the true story.

I think my first Time cover is being shared and posted over and over again because it stands the test of time. People still feel the same rage. Imagery is still giving the same energy, because people are going through the same things. Freddie Gray was murdered by police in 2015, and the same thing happened to George Floyd five years later. We are in the same place that we were five years ago. The images speak the truth. Photography is more than just a photo, it speaks to the truth of what we’re dealing with.

We see you still love your Leica camera! What continues to inspire you to pick up the camera and get the shot, especially these past few weeks?

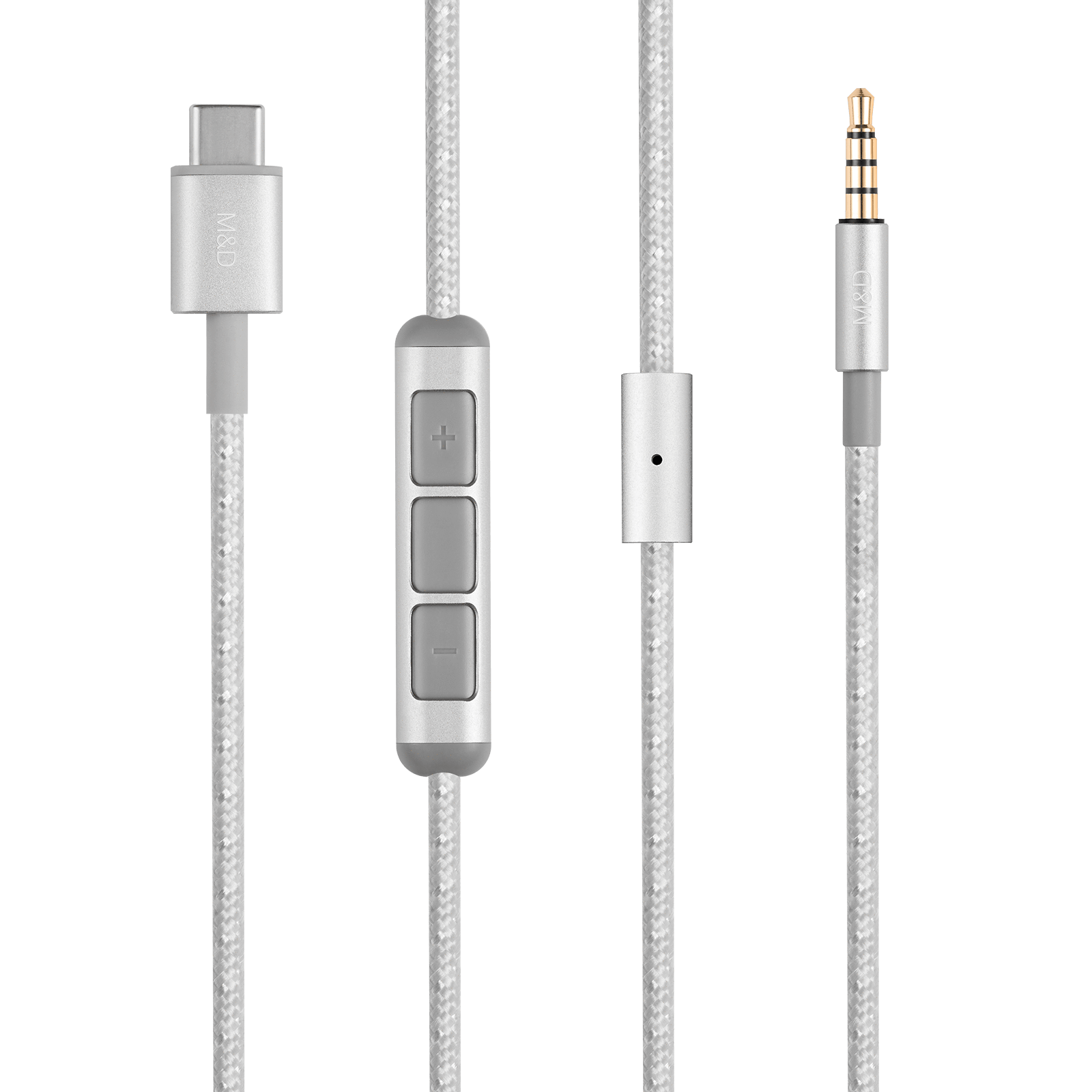

Equipment is supposed to be an attachment of you. My talent lies inside my head and eyes, but my weapon is the camera. My equipment needs to relay my messages to the world. Photography allows me to digest the world, and regurgitate it through the art form of photography. When people see my images they get an impression of what I’m feeling, thinking and seeing. I remember getting my first Leica, which was a Leica Delux point-and-shoot. Looking at the history of Leica and what that brand is all about, knowing that at one time Gordon Parks used a Leica is really inspiring. A few years ago I met another photographer from West Baltimore who had his equipment stolen. Given my circumstances and where I was at in life in becoming the artist that I am today, I knew I’d get another camera. So I gave him my Leica and used my phone to shoot for a while. Then I met Swizz Beats at the Gordon Parks Gala, and he gave me my first digital Leica, the Leica M8. It’s in great condition, and I shot with that for a while. I love that it gives me a nostalgic feeling. I’m only worried about getting the shot. It’s all manual, so I don’t have to deal with a bunch of motors or autofocus. My camera puts me in the moment. Photography is a form of meditation for me. When I’m shooting it’s me, my camera and my subject. After my Leica M8, I saved up and bought my Leica M240 from Leica DC. I can’t see myself shooting with anything else because of the build. I’ve gone to protests with it, I’ve dropped it – it’s a solid camera. It’s an intimate camera, and definitely not for everybody. When I shoot protests, I spend time with my subjects. I don’t think I’ll shoot with anything else. It’s my best friend.

You’ve taken up painting as a new medium. What promoted this exploration and how does photography impact your new art?

I initially picked photography because it was my only outlet to create. But, photography only allows me to release certain emotions. With other mediums I can release a different kind of energy. For instance I’m in Baltimore right now. I still live in Baltimore, I’m from the hood, and I haven’t changed, no matter my Time Magazine covers or a blue check on social media. Last year I buried ten of my friends, thanks to gun violence. These were people in my community, who I grew up with that I loved dearly. All photography allows me to do is look at images and miss my friends. So I had to find other means to emote and create. I picked up sculpture, and built a vacant house inside a museum to reflect the mass-vacancy and homelessness issues in Baltimore. I started painting because I have emotions I can’t get out through photography. I just moved into one of the homes of my mentors, artist Chris Wilson, to study painting underneath him in his studio. Art is my therapy. I need it to deal with every aspect of my life, and photography only allows me to deal with what’s in front of me. Painting allows me to deal with things after the fact.

Images often play an important role in telling the story of a movement, most notably Black Lives Matter. How has the role of photography evolved over the past few years, and adapted to push current social issues?

Photography has been commercialized for so long – there are people all over the world that document their lives. If you look at the history of photography, it was only for the rich. Now you fast-forward and photography is super accessible. With Instagram, people who never felt they were part of the conversation are now taking on an active role. Photography allows everyone to speak for themselves. When I was shooting Baltimore five years ago for my first Time Magazine cover, the rest of the country was not in uproar – it was just Baltimore. And before that, it was just Ferguson. In Baltimore we were alone – it was just us, so it’s hard to compare my photography to anyone else because there were not a lot of people on the ground shooting what happened. I see a lot of photographers inspired by my work in Baltimore, especially now that it’s happening in their own cities. It’s a formula. Photography is activism, it’s powerful. We don’t listen to the media anymore. Five years after Baltimore, we’re looking at who is on the ground and who is actually shooting this stuff. If you look at all the publications that are getting in trouble for not hiring Black photographers, you can see journalism evolving. We’re breaking our own stories on social media with our own cameras.